Switching off analogue radio alone would make little difference to overall energy consumption, and could even lead to an increase in carbon emissions.

There can be little doubt that the BBC’s proposal to shut down longwave transmissions from 2025 is primarily a cost-cutting exercise. As well as the (undisclosed) monetary costs of running the three longwave broadcast sites at Burghead, Westerglen and Droitwich that provide national coverage, the BBC has suggested that there would also be a saving in carbon costs by switching off the energy-hungry transmitters.

However, it is our contention that switching off longwave radio would in fact save only a minimal amount of energy – and could in fact lead to an increase in emissions. This article will explain why.

In Short:

- Switching off AM (let alone LW) would make only a very small energy saving compared to the overall energy use associated with BBC radio distribution and listening

- Most AM receivers actually use a lot less energy per hour of listening than computers, televisions, ‘smart speakers’ or digital radios

- Energy use might in fact increase, therefore, if listeners migrated from AM radios, especially if they used ‘smart speakers’ or televisions instead

- To maximise energy savings, the BBC should switch off radio through digital television, and encourage listeners to use AM radio rather than internet streaming wherever possible

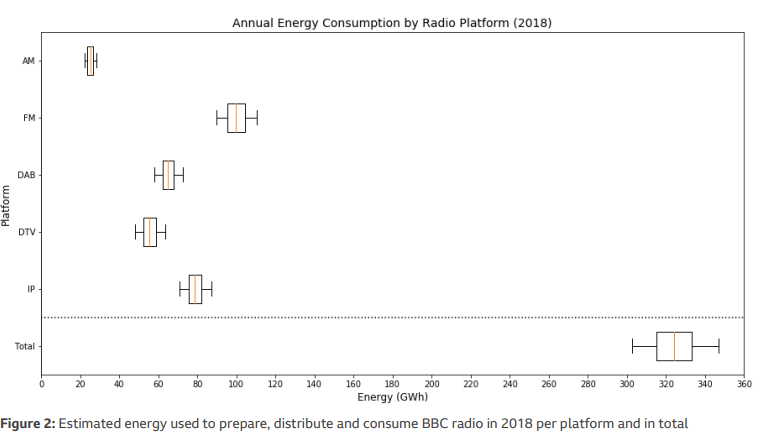

AM has the smallest carbon footprint of all BBC radio output

In 2020, the BBC published a white paper entitled The energy footprint of BBC radio services: now and in the future. This paper modelled the energy required for both distribution (transmission masts, internet servers etc. used to provide audio content) and consumption (radios, computers and other devices) for several different ways of listening to BBC Radio content. The report showed that AM radio (which includes longwave) was associated with by far the lowest overall energy consumption, compared to FM, DAB, DTV (radio through digital television) and internet listening in 2018. Their graph (below) shows that by far the biggest energy saving would come from switching off FM, not AM. This is because AM (and especially longwave) requires far fewer transmitters than FM or DAB to cover the same geographical area, which more than compensates for the increased efficiency of DAB broadcasting, which allows multiple stations to broadcast on the same frequency.

Source: Fletcher & Chandaria, 2020

However, the report went on to claim that the energy use per listener hour on AM radio was much higher than on most of the other platforms. This was because it was assumed that AM listenership was much lower than that on other platforms, on the basis of RAJAR listening figures. Hence, there might be a big energy saving by getting the few AM listeners to migrate to other ways of listening to the radio and switching off the few AM transmitters.

We disagree with this analysis. In the BBC paper, because RAJAR does not distinguish between AM and FM listeners, the LW listenership for BBC Radio 4 was arbitrarily assumed to be 10 per cent of Radio 4’s overall analogue listenership – i.e. FM and LW. No justification was given for this figure. Given that RAJAR does not survey listeners in areas that depend most upon longwave – the countryside and areas with poor reception – it is unlikely that this represents the true number of longwave listeners. Furthermore, many people still listen to Radio 5 on mediumwave sets they may have owned for years. The BBC needs to undertake a thorough survey of radio listening habits in all parts of the country before it can make any claims about the number of listeners to AM radio. If there are more listeners to AM radio at present, the energy cost per listener-hour will be lower.

AM Receivers save energy

Another caveat with the BBC report – which is admitted during the discussion – is that the estimate for the energy used by AM radio sets was not robust. Indeed, the report makes out that, collectively, FM and AM radio receivers used more energy than DAB, televisions used for radio, and internet radios in 2018. This is partly because of the high listenership of especially FM radio, but assumptions are also made about the power and especially standby-power of analogue radios that do not stand up to scrutiny. As the authors admit, ‘the on and standby power values for all radio sets were based on measurements from a small sample size, and had high uncertainty.’

Unlike computers, televisions, almost all DAB radios and essentially all ‘smart speakers’, which are designed to be kept on ‘standby’ mode all the time, very few analogue radios have a standby feature at all. Given that it was estimated that nearly 40% of the energy use associated with radio listening could be attributed to devices on standby, this is extremely significant. If everyone switched to analogue radios with no standby, this energy would be saved overnight. Furthermore, even when switched on, AM receivers use substantially less energy than most digital ones. A portable longwave radio can run for months of frequent use using a single set of 1.5V AA batteries, where DAB radios with their more complicated technology require frequent recharging. Internet-connected devices, and especially ‘smart speakers’, use even more energy. The BBC report itself admits that most internet-connected devices use more energy than analogue radios, even whilst vastly overestimating the energy requirements of these radios. The paper states that EU regulations require a standby power of no more than 0.5 Watts for non-internet-connected devices, but that this limit is as high as 3 to 12 W for internet-connected ones. Staying perpetually connected to the internet requires a lot of electricity.

All in the transmission

It is therefore safe to conclude that much of electricity associated with AM radio listening goes into the AM transmitters, not the receivers. This is in contrast to the overall message of the report, which finds that for BBC radio as a whole the majority of energy use is in the consumption rather than the distribution stage. This is because of the high energy requirements of internet-connected devices, DAB radios and digital televisions used to listen to the radio. AM is therefore an outlier in this regard: in general, more energy is used by listening equipment than transmitting equipment. According to the BBC paper, the amount of electricity used by data servers for internet radio is also relatively small compared to the energy consumption of the computers and ‘smart speakers’ used to listen.

This is not to say, though, that switching off AM transmitters would therefore be good for the planet. On the contrary, it would mean that all those AM receivers using very little electricity would have to be replaced by digital or internet receivers, which use a lot of energy. It is our contention that the energy savings from switching off the three national longwave transmitters – which are very efficient because they cover the whole country from just three sets of masts – would be outweighed by the large energy costs of listeners switching to other forms of radio receiver. The most energy-efficient option would in fact be for everyone to listen to BBC Radios 4 and 5 on low-power analogue receivers. This would not be possible if longwave was shut down.

Scenarios for the future

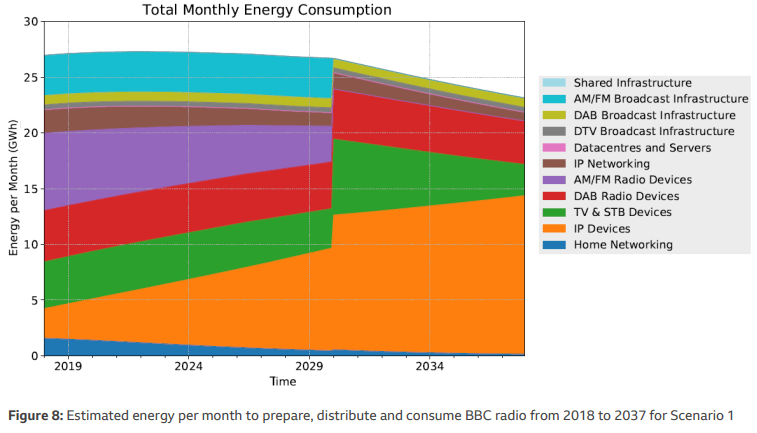

In the BBC report, four different ‘scenarios’ are put forward for the future, and the energy costs of each compared. ‘Scenario 0’, or ‘business as usual’, saw all current radio platforms maintained. This has a current energy cost of around 27 Gigawatt-hours per month, and would be projected to barely change by 2037, the end of the forecast period. Compared to this, ‘Scenario 1’ in which AM and FM only were switched off made barely any difference to begin with to energy consumption, since the energy savings of switching off the transmitters were used up by increased energy consumption from internet-connected devices. Indeed, there was only a drop in energy consumption at all by 2037 because the energy-efficiency of radio through digital television (DTV) was projected to increase (see figure below).

Source: Fletcher & Chandaria, 2020

Hence, switching off analogue radio makes practically no energy saving overall, according to the BBC’s own report. This includes the assumptions we have critiqued above regarding the energy use of analogue radios and the listening figures for AM radio. If both of these are taken into account, it is likely that simply switching off analogue radio would increase carbon emissions because the orange ‘IP devices’ (internet-connected devices) energy consumption would be even higher, whilst the purple ‘AM/FM audio devices’ contribution would be less.

Scenario 2 explored the effect of switching off both analogue radio and radio through digital television (DTV). Here, there is a marked gain in energy savings, as can be seen below.

Source: Fletcher & Chandaria, 2020

The obvious conclusion from these two figures in combination is that switching off radio through digital television (DTV) would produce significant energy savings, whereas switching off analogue radio would not. DTV also has high monetary costs for the BBC because it has to pay for its television and radio slots on satellite television. A very small proportion of listeners use this service, and it has a disproportionately large energy cost. Indeed, even the latest RAJAR figures – limited as they are regarding coverage of areas with poor reception – suggest that only 3.3 per cent of radio listening takes place via DTV, compared to 36.2 per cent for analogue radio. Unfortunately, the BBC paper did not model the effect of switching off DTV alone, but this conclusion is inescapable from a comparison of the two figures.

Interestingly, Scenario 3, where DAB was also switched off, showed only a very small decrease in energy consumption compared to ‘business-as usual’, showing that an internet-only BBC would be significantly more energy-intensive than one that includes DAB – and, we argue, analogue radio.

Conclusions

When it comes to saving energy, figures from the BBC’s own white paper point towards the conclusion that switching off FM and AM would do little to decrease overall energy consumption. Those figures do not take into account the energy costs of replacing analogue devices with digital or internet-connected ones, which would further increase the toll on the environment, especially as these devices require more complicated circuitry and are more energy-intensive to produce.

Furthermore, we are of the opinion that the BBC paper has underestimated longwave listenership, especially in rural areas; and has overestimated the power consumption of analogue radios, especially portable ones; and that consequently switching off analogue radio would increase carbon emissions. These are our conclusions:

- Switching off AM (let alone LW) would make only a very small energy saving compared to the overall energy use associated with BBC radio distribution and listening

- Most AM receivers actually use a lot less energy per hour of listening than computers, televisions, ‘smart speakers’ or digital radios

- Energy use might in fact increase, therefore if listeners migrated from AM radios, especially if they used ‘smart speakers’ or televisions instead

- To maximise energy savings, the BBC should switch off radio through digital television, and encourage listeners to use AM radio rather than internet streaming wherever possible

Please support the Campaign to Keep Longwave, and help keep this nationally important piece of infrastructure running for the future. Rural communities, the UK’s resilience to external threats and the climate will all benefit.

Sources:

- Fletcher, Chloe & Chandaria, Jigna. The Energy Footprint of BBC Radio Services: Now and In the Future. October 2020. https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/rd/pubs/whp/whp-pdf-files/WHP393.pdf (accessed 05-12-2024)

- RAJAR. RAJAR Data Release Q3 2024. October 24th 2024. https://www.rajar.co.uk/docs/2024_09/Q3%202024%20Chart%204%20-%20BBC%20Comm%20Platform%20Share.pdf (accessed 05-12-2024)

Leave a reply to James Birkett Cancel reply